Χαιρετε! Chairete! Rejoice!

AND WELCOME—to an introduction to A Cavalier Introduction.

First of all things first as you begin adventuring through Ancient Greece, time. Time, which is as subjective as history. Recall your Einstein: ‘The distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.’ Or open up your Hindu scripture and find that Time it was who ordained Death as the master of all and the destroyer of worlds. Or ideally, start with the Greeks, for whom Time was the father of the gods and devoured his own children—Kronos, conquered by Zeus so that Time’s power might not be unlimited.

Time & ‘Antiquity’.

And now that you’re thinking on a large enough scale, I want you to rid yourself at once of any time-notion of “Antiquity”. There was no such thing. Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome were as different from each other in their forms and their aims as were Renaissance Italy and Medieval Cambodia. Rome’s core values were order, hierarchy, and obedience. As you’re about to discover, the Greeks strove for wisdom, decentralisation, equality, and freedom. Above all the Greeks stood and fought for justice. They also invented the very concept—while the Romans used their word ‘liberty’ as propaganda, a pretext for invasion, subjection, control. Yet people seem to adulate that which would enslave them, and the study of Rome is more popular.

As well, Greece and Rome are separated by centuries, four and a half of them. From 480 BC, the beginning of Classical Greece, to the triumph of Julius Caesar, stand 436 years. It’s the same amount of time that stands between us and Elizabeth I, and in fact by the time the Romans and Greeks meet one another, the events of this semester will long have run their course. We are not Shakespeareans and neither the Romans nor the Greeks were ‘Ancients’.

Space and Equality.

After time, we grapple with space. A full third of Greece is bare rock upon which nothing can grow or graze. At the start of our timeline there are half a million Greeks living among that rock in 40 cities. Much more critical to the Hellenes is the sea, across which they will sail to fight and trade, and the control of which will determine the misfortunes of men and cities. By the end of our semester environmental degradation will have set it in and there’ll be eight million Greeks living in a thousand Greek cities from Spain to Afghanistan—at half the population density that Greece has today.

In their respective periods the Greek economy outperforms the Roman, and our Athenians will attain a level of general prosperity akin to Florence in the 15th century and Holland in the 17th. Under the Roman Empire roughly 90% of the population lived at subsistence level and from 300AD onwards these were hereditary serfs. In Athens 49% of people lived at subsistence level and 50% of the population were comfortably middle class. The top 1%, the elites, did own 30% of all the private wealth (they own 32% of it in 21st-century America), but in Athens 70% of the land was owned by 60% of the population and as few as 20% of Athenians owned no land at all. In England today 50% of the land is owned by less than 1% of the population. While Rome was run by and for its ultrawealthy senatorial class, throughout most of our semester Greece will have no comparative millionaires. Only in our final two weeks will Greece leap straight to having one (multi) billionaire.

That is, Ancient Greece is a time and a place unto itself—primordial, disparate, prosperous, equal—with a culture so eternally enriching that it was adopted almost whole by the always barbaric Romans. The two were themselves, distinct and critically dissimilar. And with time and space—and their distribution—dealt with,

Splitting the Hellenic Atom.

You, splendidly curious person, are about to become very well acquainted with what centuries of the best and the brightest have referred to as ‘the Greeks’, though they called themselves Hellenes. If nothing else, the Hellenes are a fascinating people. They swore oaths over upturned shields filled with bull’s blood. Instead of saying, ‘Jesus Christ!’ when someone pissed them off, they yelled, ‘Herakles!’ Their women employed Brazilian slaves to singe off their pubic hair and their many dildos were encased in dog leather.

But as well as strange they were ingenious. They were insatiably curious. They were noble and mighty. Preferring always to fight rather than flee, to inquire rather than to believe, to change rather than stagnate—the Greeks are, to us cowardly and believing stagnators, the most dangerous people ever to have walked the earth. But their danger is not to be measured in the likelihood of their taking a machine gun into a high school or their scepticism of vaccine mandates. The danger of the Hellenes lies in their liberating potential. To understand Greek culture, to split the Hellenic atom, is instantly to become free—in 2024 the most dangerous and endangered of existences.

As well as the Greeks themselves, you are soon to meet several of the brilliant minds who devoted their lives to studying them. The quality of Ancient Greek scholarship is unparalleled in any Humanities discipline and there has accumulated 150 years of it. Some of the most intelligent pens in all European languages have been dedicated to translating, cataloguing, interpreting, the Hellenes. In reverse chronological order Walter Burkert, E.R. Dodds, C.M. Bowra, Werner Jaeger, Gilbert Murray, Burckhardt, are among the best of them. To the end of this essay I’ve appended an uncritical bibliography—those secondary books, essays, & articles from which the semester’s essays are derived. If you’d like to read any of those works I have almost all 170 of them available in digital format.

Then there’s Nietzsche, the strangest and most radical Greek interpreter but also the most perceptive and the bravest. It was Nietzsche who admitted what nobody else would see—that as well as enlightened and symmetrical and perfect the Greeks were mysterious, dark, and cruel. It was he who finally enabled us to approach a full understanding of the fullness of the Hellenes and therefore of ourselves.

Through their, and my, instruction, by the end of this semester you will have a better understanding of the Ancient Greeks than a 2nd-year undergraduate. If you have time for extra reading, you will come to know more about Ancient Greece than many sinecured historians of the period. And in order to begin your Hellenisation, we must begin with the very early history, for only upon that framework can valid enthusiasms be built.

The Bronze Age Collapse.

From 2500 B.C. onwards for at least eleven centuries a civilisation called ‘Minoan’ existed on Crete. Between 1600 and 1000BC there also arose on the Greek mainland a civilisation we call Mycenaean. This eventually supplanted and absorbed the Minoan, and the language of the supplanters is the very earliest form of Greek. It’s called Linear B, and was deciphered by a nerd in 1953. 𐂖 is Linear B for wine. ‘𐀁𐀩𐀄𐀳𐀫’ transliterates to ereutero, and signified people exempt from certain palace tributes. Ereutero is etymologically the predecessor of eleutheros, a free person, and eleutheria, freedom—words about which we and the Greeks will have much to say.

So in this our first week we perform the ultimate Western throwback: to 3200 years ago. The Mycenaeans battled in chariots, made fancy bronze swords, invaded distant non-Greek cities. Their power and societal structures revolved around kings and their hilltop palaces. Their most renowned king was Agamemnon, lord of the civilisation’s largest palace, at Mikines (the city Anglophones call Mycenae) perched still today upon an outcrop half way between Sparta and Athens. You may have heard of Mikines’ most notorious war: waged against a city called Troas—Troy—in modern-day Turkey.

But the archaeological record tells us that from 1200BC to 1000BC the number of occupied Mycenaean settlements dropped from 320 to 130 to 40. The population declined by anything from 75 to 90 percent. Even areas that escaped physical devastation, like Athens, suffered complete political collapse. Why? As with most things we would most like to know most about, we don’t know. One theory is that a large migration of angry sea peoples wreaked a critical mass of havoc. Most Mycenaean palaces show evidence of being torched to the ground in their final days. In fact the only reason we have any Linear B at all is because the clay tablets upon which it was written were kilned in the fires that destroyed the cities that produced them. What a melancholy end—and poetic source for history to rely upon.

Another theory is an all-out systems collapse. The 2nd millennium BC saw a globalised world reaching from Sardinia to Afghanistan and centred geographically on copper-producing (and copper-named) Cyprus. That millennium, the Bronze Age, was as dependent on tin as we are on oil—tin which is the 10% to copper’s 90% in the manufacturing of bronze. Tin had to travel 2000km from Afghanistan before it could be smelted in Cyprus, and Cyprus was invaded by the Hittites in the last century of the Bronze Age. This perhaps disrupted the trade routes that enabled that semi-globalised world to till and to kill.

But for one reason or another, one by one the eight civilisations that comprised the Bronze Age collapsed. Whyever it ultimately disappeared, by 1050 Mycenaean Civilization was gone. The unhappy few who managed to stay alive cowered for centuries behind their city walls as Greece entered the 250ish years of what historians call its Dark Age—a period for which we know no history whatsoever. Even the ability to write was lost.

The Agonal Age.

Then in 776BC somebody found a rusty zippo and the lights came back on. 776BC is the first definite date in Greek history, when the All-Hellenic games were organized as a regular event upon the site at which Zeus wrestled Time for control of the universe—Olympia. Yes, Greek history begins with the Olympic Games, and competition and contests—the agon—will always remain vital to its culture. (776 BC is also the first precise date in Chinese history. They that year recorded—and angrily denied any wrongdoing in—a solar eclipse. East and West are precisely the same age.)

In about the same decade the Greeks took the Phoenician system of writing, which consisted solely of consonants, and added to it vowels. S t s t th Grks tht w w wrtng s w knw t. With the Phoenician symbols came their Phoenician names: ‘Aleph’, for ox, ‘bet’, for house—and these were turned into Greek syllables: alpha, beta, and so on. So the Greeks literally invented the alphabet—crucially an alphabet that was accessible to everyone, for Hellas had no guild of scribes nor caste of priests to which knowledge of writing was restricted. It will even become a popular insult to call someone agrámmatos, alphabetless: ‘Look at this f-----g agrámmatos!’

(I’m hoping that along the way you’ll take the time to learn the Ancient Greek alphabet. It’s only 24 letters, and is outlined on the first page of your Apophthegmata. Knowing it greatly enriches your historical experience.)

From around the same time—as which year? I do hope you’re paying attention—comes the poetry ascribed to Homer, which we’ll explore in great detail next week. For the next 453 years Homer’s epic poems, coupled with Hesiod’s explanation of the ruling powers of the universe, formed the worldview, ideals, and education of a single many-islanded land—Hellas—littered all over with poleis, the Greek plural for polis: city-state. At the end of our timeline, King Aléxandros the Third of Macedon attempts to export this culture to beyond the known world, and in exporting it, kills it.

So in our semester we go from the world that created Homer to the world that Alexander left behind: roughly from 800 to 300BC. 500 years, all of which are in the BCs, so I’ll drop that superfluous addition.

The Axial Age.

Karl Jaspers once set out to find an ‘axis’ of world history. Taking into account simultaneous philosophical developments in China, India, Persia, Israel, Greece—he found his axial age in the precise period that we are to cover, for ‘it was then that the man with whom we live today came into being.’ The communist György Lukács claimed that the cultural development of the Greeks—from epic to tragedy to philosophy—is in itself a philosophy of history, that the stages of Greek history represent the timeless development of the outward and the inner lives of all humanity. In simpler terms, even as individuals we go—as you might see Hellas go—from an energetic and unthinking youth, to a grand and consequential adulthood to an overly reflective and withdrawn old age.

As well as in its relation to literature and human life, Lukács’ assertion is true for several other aspects of Greek history. As only one example, down the centuries the Homeric virtues performed by the individual in service of himself become virtues owed to and rewarded by his polis. When the polis repeatedly fails to return its promises, those virtues are repurposed to serve as coping mechanisms in a world of neither heroism nor cities. So as the Greek goes from epic to tragic to philosophical—and from youth, to adult, to geriatric—he also goes from heroic individual to heroic citizen to homeless mystic.

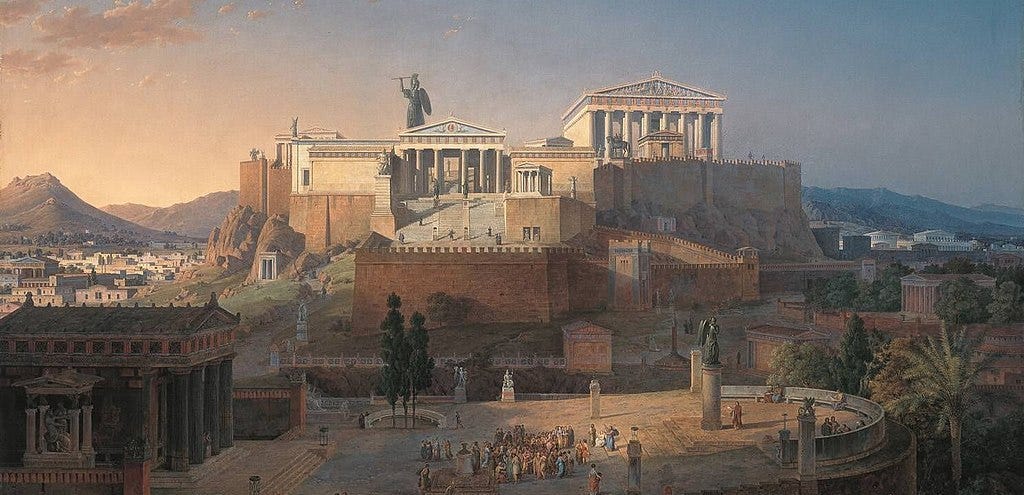

The zenith of these trajectories is traditionally taken to be the middle 400s, more precisely the year 430—when Perikles, Pheidias, and Sokrates could attend a play written by Sophokles in the Theatre of Dionysus beneath the brand-new Parthenon. It is—with its paragons of democracy, art, philosophy, poetry, architecture—a period absolutely unparalleled in the history of the world. Renaissance Florence had no poetry and Elizabethan England had no philosophy. I don’t even want to mention our own architecture, but we in 2024—beaming as we might be—have added to human life break-dancing, butt implants, and the demonisation of jaywalking.

So 5th-century Greece, Athens around the year 430, is what is termed the ‘Classical Age’ or even the ‘Golden Age’. It was, in the words of Bertrand Russell, an age in which it was possible ‘to be both intelligent and happy, and happy through intelligence.’ A rare occurrence indeed, and a worthy aim upon which to set our own sights. Whether Russell’s estimate is correct we shall find out for ourselves, though our primary evidence will be scant. From that 5th century we possess about 5% of the literature that we know was produced. Of the earlier Greek centuries we have not nearly as much and almost all of what we do have from any time comes from Athens—for it’s in Athens that the most nourishing elements of the Ancient Greek soul concentrate themselves.

The intertwining threads of these developments—historical, material, cultural, mental, and spiritual—are what amount to our A Cavalier Intro to Ancient Greece. And in an Austin-Powers nutshell the following is both the chronological narrative and historical hypothesis to which this Introduction is going to hold. 9 separate weeks of New Cavaliering, 9 points in need of proving, 9 stages in the cultural development of Ancient Hellas. All are, of course, open always to challenge:

· In recalling the oral memories of Mycenaean Greece, Homer composed poems of such extraordinary worth that the actions and values of their characters formed the values of Greek individuals for centuries to come. Chief among these values was Achilles’ embodiment of excellence and glory, and his insistence on the just distribution of the rewards of toil.

· Hesiod outlined an ordered world and a priestless religion in which the gods maintain an equilibrium of worldly justice—an equilibrium which the aspirations of man should never aspire to upset.

· Aristocratic political monopolies were supplanted first in Sparta, where the Homeric ideals of excellence and glory became rewards bestowed by the polis; at Athens Solon then transferred Hesiod’s conceptions of justice and equilibrium to the same.

· Athens took its justice-system (its politics) further away from tyranny by instituting a program called isonomía—a system which ensured all citizens played a part in writing the laws under which they lived and in deciding how justice should be striven for and maintained.

· The Persian Empire, with an entirely different view of the world and of man’s place in it—in many ways an epitome of not-Greece—spends 33 years attempting to subdue all of Hellas, and fails.

· Victory over Persia instilled in the Athenians a pride in their culture and their ideals, by which—through decades of exploration and expansion—they created tragedy, comedy, history, philosophy, architecture, beauty, & education.

· Philosophers moved from the periphery to the centre and in Athens reappraised all existing ideas. Protracted disaster in Greece, and Sparta’s military victory over Athens, led to a questioning of all that made freely inquiring Athens great—and to uncertainty about the benevolence of the gods and their just distribution of the rewards of virtuous striving.

· Upon inheriting hegemony of Greece, Alexander III of Macedon conquered the Persian Empire then invaded India. His life transcended, or broke, the limits set on what a Greek ought to aspire to achieve. He and his successors divided the world into empires in which they ceased distributing rewards according to Hellenic principles of justice.

· In response to a new chaotic and citiless world, philosophers sought a consolatory existence through internal independence from external events. The Greeks soon transferred all value from tangible real life to the philo-sophical idea of an eternal one, wherein justice might be meted out more fairly. The values which created and ruled the Greek world thus consumed themselves and expired.

Such is the lengthy hypothesis we are now to test. It runs through almost all of the major events and developments and individuals in Greek history.

The subjects I’m going to emphasise over the next 9 weeks are perhaps not the most mainstream ones. Whole works of academic tedium run volumes without mentioning them. Nor are they perhaps the most modern. Though I keep up with the latest scholarship, I pay no attention to the fads of gender or race. But A Cavalier Intro to Ancient Greece contains a complete historical portrait of the period and the subjects I focus on are those which most vivified and distinguished the Ancient Greeks. So they are the subjects that stand the greatest chance of re-vivifying us. They are also the subjects that form the distinguishing essence of Western Civilization—the thunderbolts that animate our mongrel peninsular life, the burn scars that mark us out from the fellaheen of the East, the worshippers of the South, and the wildmen of the North.

The youth, the originality, the clarity of Greek life have a potency which, I hope you’ll swiftly see, is difficult to deny and impossible to resist. Aside from the realms of politics, philosophy, art, history, tragedy, comedy, and naked exercising—I above all hope that the Greeks, having thrived as THE superlative humans, might through the next 9 weeks teach you a few of the secrets of recovering what it means to fully live. They were freer than we are—but free by exertion, not from exertion. They considered it preposterous for someone to abide by laws they did not make for themselves. Eating directly from the soil and the sea, they lived longer and taller lives than most of us can hope to. They valued neither words nor action by themselves, but held greatness to consist in their combination. In being comfortable with eternal death they were joyous in transient life. They thrived among subtle paradoxes and felt no need of seeing these reduced to destructive solutions. Before Sokrates they were both intelligent and wise, and knew instinctively the proper ends of life. It is my adamant belief—and my own hopeful personal embodiment—that it’s possible to not only live as an individual, but by returning to original principles to constantly rejoice as one.

This, is the great danger of the Greeks—danger from which they themselves urge us never to shrink. Sokrates, whom you’ll meet in Week 7, had a word for this process: ανάμνησις. Anamnesis, a remembering of things forgotten, in which the philosopher acts not as a teacher but as a midwife. I here hope that in receiving the legacy of the Greeks you remember some of what has been forgotten—and that my hands will be for five fortnights covered in placenta.

And with our hypothesis soaked in afterbirth—a hypothesis which is also our historical narrative—let us now spend the better part of two months testing whether its umbilical cord allows it to remain connected to its omphalos, to its navel. Let’s see if its rhythmos stays within the harmonious confines that Fate has given it—if our vision of the Greeks’ essential inner nature, their φύσις, proves to be true.

Let’s see if indeed the history of Ancient Greece contains as many ideas worthy of consideration as I believe it does.

Let us begin,